By Tony Azamfirei

Few subjects connect neuroscience, psychology and philosophy quite like psychedelics. This article offers a concise introduction, exploring questions such as: What are psychedelics? What is the chemistry behind them? Why is there an upsurge in interest in their potential uses? Future pieces will examine each aspect in greater detail.

Introduction

The word psychedelics is associated with a wide range of meanings and interpretations. For some, it represents a recreational substance linked to leisure or escape. For others, these compounds hold the promise of treating conditions once believed to be untreatable. To understand what psychedelics truly are, it is necessary to explore the origins of the name itself. The term was first coined in the 1950s by psychiatrist Humphery Osmond in a letter to the famous dystopian author, Aldous Huxley.1 The word “psychedelic” is derived from the Greek word psychē (ψυχή, translated as “soul” or “mind”) and dēlein (δηλειν, translated as “to reveal” or “to manifest”). The resulting term literally translates to ‘mind-manifesting ‘ or ‘soul-revealing’.1 The meaning itself is enough to make one wonder, do these substances truly reveal the deepest secrets of our soul? To begin answering this question, we must first explore the history of these substances.

A Brief History of Psychedelics

Humanity’s relationship with psychedelics is ancient. Numerous cultures, such as the Maya, Zapotec and Aztec, used psilocybin-containing mushrooms and the seeds of ololiuhqui (which contain lysergic acid amide)2 for ritualistic, divinatory, mystical and sometimes healing purposes.3-5 Unsurprisingly, these substances were commonly believed to possess divine properties, since they produce profound alterations in thought, sensory perception, mood, intuition and the experience of self, space and time.6 Such effects were famously described by Aldous Huxley in his book The Doors of Preception.7 Despite this rich cultural history, especially in the Americas, the westernisation of society and following prohibitionist policies led to universal bans. The UN Convention of Psychotropic Substances in 1971 required member nations (132 at the time) to prohibit psychedelics under almost any circumstances.8 As imaginable, this led to a decrease in the use and research in psychedelics and their potential uses. Recently we have witnessed an increase in interest even some relaxation of certain policies, allowing more research to be conducted. Various cultures have associated plants containing psychedelic compounds with religion, rituals and spirituality due to the effects they have on human consciousness.

The Chemistry Behind the Psychedelic State

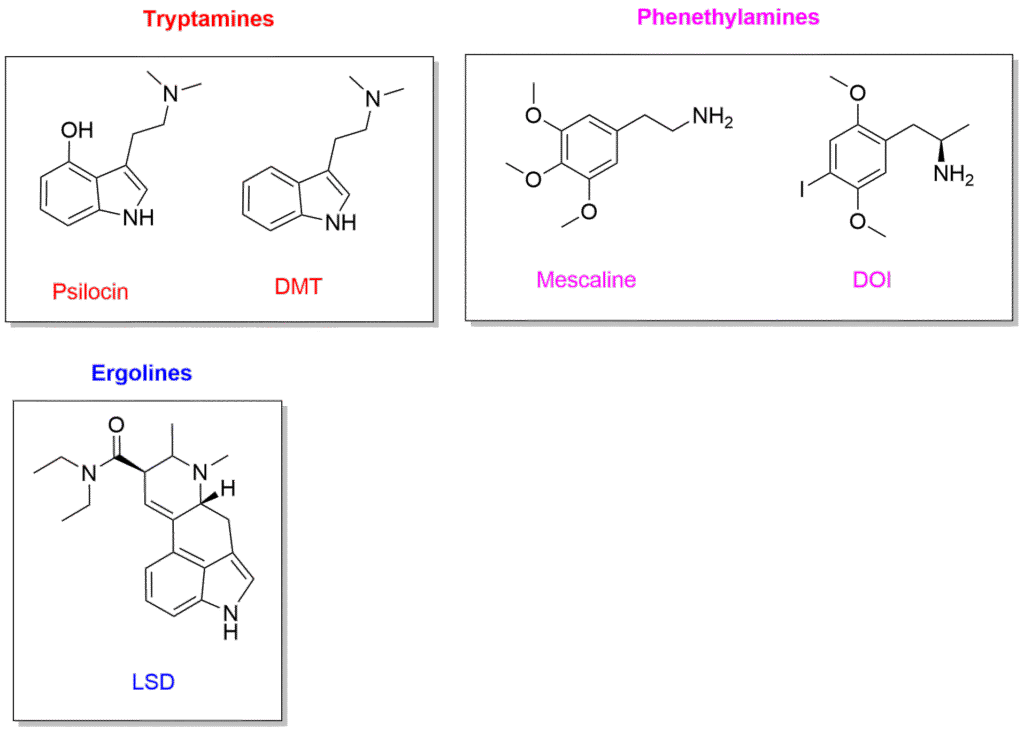

Chemically, classical psychedelics form several families. They can be divided into three categories based on their chemical structure: tryptamines, ergolines and phenethylamines (as illustrated in Figure 1).9 Tryptamines are built from tryptamine; a compound also found in serotonin and includes psychedelics such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and psilocybin. Phenethylamines (such as mescaline) are based on phenethylamine, resembling a structure closer to dopamine. Ergolines, the family that includes D-lysergic acid (LSD), are a hybrid of tryptamine and phenethylamine frameworks.

Figure 1: Chemical structure of classical psychedelic categorised in their chemical structure families (tryptamines, ergolines and phenethylamines).9

As expected, due to the differences in structures of these compounds, they do not all act on the exact same receptors with similar affinities. For example, psilocin (converted from psilocybin in the body) binds with moderate affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C receptors,10 but has relatively low affinity targeting dopamine and adrenergic receptors.9,11 On the other hand, D-LSD (the enantiomer of LSD that is a hallucinogen) has modest affinities for dopaminergic receptors9 along with high affinities for 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT7 receptors.11,12 These difference contributes to different active doses ranges in humans and to some qualitative and quantitative differences in the experience of taking each drug.

Despite the differences in their chemical structures, most classical psychedelics act as an agonist on a common molecular gateway: the 5-HT2A receptors. These receptors have been established, particularly in the cerebral cortex, as the primary molecular targets required to induce hallucinations in human beings.13,14 The activation of 5-HT2A receptors results in a distribution of the brain’s normal filtering and integration of sensory and cognitive information. This alters the balance of excitation and inhibition in cortical circuits, leading a ‘loosening’ of the brain’s predictive coding mechanisms.15,16

While this article discusses only classical psychedelics, it is worth noting that there are other psychoactive compounds that can induce ‘psychedelic- like’ effects on the user named non-classical psychedelics. In future works this will be looked at in greater detail.

What Do Psychedelics Do to Consciousness?

Modern neuroscience now provides a language to translate what ancient traditions could only describe metaphorically. Through their agonist activity at 5-HT2A receptors, profound alterations in consciousness are induced. This leads to enhanced neuronal excitability and glutamate release, resulting in disruption of normal rhythmic oscillations and filtering mechanisms in the brain.17 This results in a derepression of intrinsic brain activity and an increase in entropy (randomness across neural networks), which loosens the brain’s predictive coding hierarchy that normally constrains perception and cognition.16 This might explain the unique emotional breakthroughs and fresh perspectives often reported by users of psychedelics.18

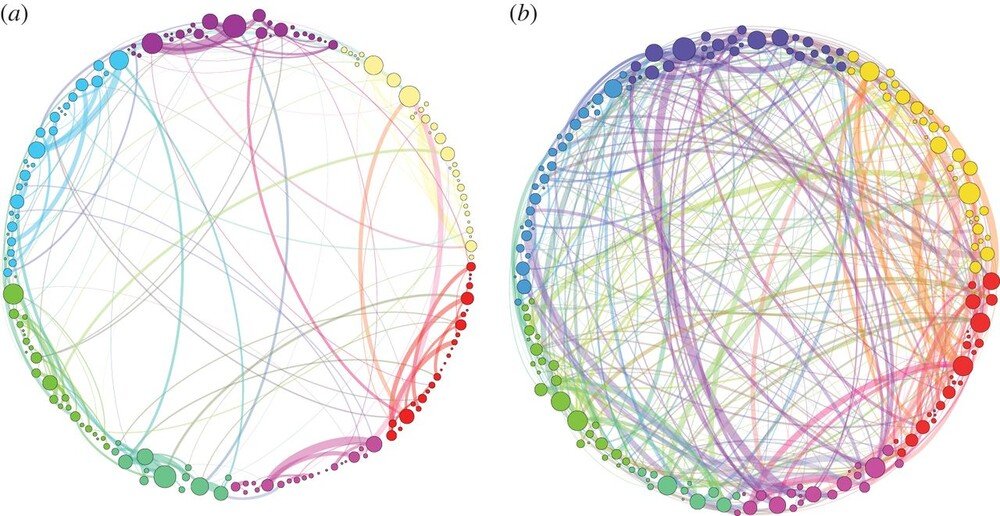

Another effect is a decrease in the activity and integrity of the default mode network (DMN), a core brain network link to self-referential thought and maintenance of the ego.19 This suppression explains the subjective experience numerous people report of ego dissolution and blurring the boundaries between self and the environment. Increased connectivity between normally segregated brain regions, as illustrated in Figure 2,20 further contributes to heightened sensory experiences, often associated with an expansion of consciousness.21,22

Figure 2: An illustration of communication between brain networks in people given a non-psychedelic compound (a) and psilocybin (b), showing a great increase in communication in b.20

Philosophically this gives rise to an interesting question: do psychedelics just distort normal brain function, or do they reveal aspects of consciousness that are typically hidden by the brain’s filtering mechanism? Your answer most likely depends on how you view the world: for the physicalist, psychedelics mess around with the fragility of our brains; for the mystic, they allow us to see a different version of reality, perhaps some may even say the ‘true’ reality…

The Therapeutic Potential

The modern resurgence of interest in psychedelics is not only fuelled by curiosity alone, but by urgent need. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that roughly 1 billion people are affected by mental health disorders.23 1 BILLION! That means roughly 1 in 8 people are affected. To put that in perspective COVID-19 has affected, as of late 2025, approximately 705 million people, and led to several lockdowns in the past few years. However, this strategy cannot be used for what is often described as a ‘silent mental health pandemic’. While the numbers are already staggering, global studies predict that incidences of mental disorders will continue to rise over the next 30 years.24

Currently treatments for mental health disorders primarily manage symptoms, with many patients experiencing only partial relief and recurrent issues.25 These approaches typically do not address the underlying issues, such as biological, psychological and social factors, resulting in a demand for treatments that can restore mental well-being at the foundations. This is where psychedelics comes in. Psychedelics offers a unique advantage when compared to current available treatments: they tackle the root cause of the problem. It has been shown that psychedelics, such as psilocybin and LSD, promote neural plasticity by enhancing the growth and connectivity of neurons, helping to ‘reset’ pre-existing dysfunctional patterns of brain activity that contribute to persistent mental health challenges.26,27 By promoting neural plasticity, it has been shown that the benefits of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy in patients suffering from addiction, depression and anxiety can last for many months or years,28-30 along with healthy people having reported an increase in well-being up to a year after exposure to these compounds in a supportive and safe setting.31-33

Conclusion

While future works will focus on subjects in greater detail, I hope this article has provided a brief overview and insight into the exciting world of psychedelics, from their history to their potential in treating mental health disorders. They invite us to reconsider the relationship between brain and mind, between subjective experience and objective reality. Whether viewed as tools for healing, understanding cultures or windows into consciousness, psychedelics remind us that consciousness and the mind are far more mysterious than we can ever imagine.

References

1 Osmond, H. A REVIEW OF THE CLINICAL EFFECTS OF PSYCHOTOMIMETIC AGENTS. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 66, 418-434 (1957). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb40738.x

2 Carod-Artal, F. J. Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. Neurología (English Edition) 30, 42-49 (2015). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010

3 R. E. Schultes, A. H., C. Ratsch. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. (Healing Arts Press, 2001).

4 Furst, P. T. Flesh of the Gods: The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens. (Praeger Publishers, 1972).

5 Lundborg, P. Psychedelica: An Ancient Culture, A Modern Way of Life. (Haoma Press, 2012).

6 Geyer, M. A. A Brief Historical Overview of Psychedelic Research. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 9, 464-471 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2023.11.003

7 Huxley, A. The Doors of Preception. (Chatto & Windus, 1954).

8 Nutt, D. Psychedelic drugs-a new era in psychiatry? . Dialogues Clin Neurosci 21, 139-147 (2019). https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.2/dnutt

9 Jaster, A. M. & González-Maeso, J. Mechanisms and molecular targets surrounding the potential therapeutic effects of psychedelics. Molecular Psychiatry 28, 3595-3612 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02274-x

10 Chadeayne, A. R., Pham, D. N. K., Reid, B. G., Golen, J. A. & Manke, D. R. Active Metabolite of Aeruginascin (4-Hydroxy-N,N,N-trimethyltryptamine): Synthesis, Structure, and Serotonergic Binding Affinity. ACS Omega 5, 16940-16943 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c02208

11 Halberstadt, A. L. & Geyer, M. A. Multiple receptors contribute to the behavioral effects of indoleamine hallucinogens. Neuropharmacology 61, 364-381 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.017

12 Nichols, D. E., Frescas, S., Marona-Lewicka, D. & Kurrasch-Orbaugh, D. M. Lysergamides of Isomeric 2,4-Dimethylazetidines Map the Binding Orientation of the Diethylamide Moiety in the Potent Hallucinogenic Agent N,N-Diethyllysergamide (LSD). Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 45, 4344-4349 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1021/jm020153s

13 López-Giménez, J. F., Mengod, G., Palacios, J. M. & Vilaró, M. T. Selective visualization of rat brain 5-HT2A receptors by autoradiography with [3H]MDL 100,907. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 356, 446-454 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00005075

14 Kometer, M., Schmidt, A., Jäncke, L. & Vollenweider, F. X. Activation of serotonin 2A receptors underlies the psilocybin-induced effects on α oscillations, N170 visual-evoked potentials, and visual hallucinations. J Neurosci 33, 10544-10551 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3007-12.2013

15 De Filippo, R. & Schmitz, D. Synthetic surprise as the foundation of the psychedelic experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 157, 105538 (2024). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105538

16 Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front Hum Neurosci 8, 20 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020

17 Nichols, D. E. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev 68, 264-355 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

18 Roseman, L. et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: Validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. Journal of Psychopharmacology 33, 1076-1087 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881119855974

19 Gattuso, J. J. et al. Default Mode Network Modulation by Psychedelics: A Systematic Review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 26, 155-188 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyac074

20 Petri, G. et al. Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks. J R Soc Interface 11, 20140873 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0873

21 Letheby, C. & Gerrans, P. Self unbound: ego dissolution in psychedelic experience. Neuroscience of Consciousness 2017 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/nc/nix016

22 Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 4853-4858 (2016). https://doi.org/doi:10.1073/pnas.1518377113

23 Cuijpers, P., Javed, A. & Bhui, K. The WHO World Mental Health Report: a call for action. The British Journal of Psychiatry 222, 227-229 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2023.9

24 Wu, Y. et al. Changing trends in the global burden of mental disorders from 1990 to 2019 and predicted levels in 25 years. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 32, e63 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796023000756

25 Lake, J. & Turner, M. S. Urgent Need for Improved Mental Health Care and a More Collaborative Model of Care. Perm J 21, 17-024 (2017). https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/17-024

26 Calder, A. E. & Hasler, G. Towards an understanding of psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology 48, 104-112 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-022-01389-z

27 Agnorelli, C. et al. Neuroplasticity and psychedelics: A comprehensive examination of classic and non-classic compounds in pre and clinical models. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 172, 106132 (2025). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106132

28 Bogenschutz, M. P. et al. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol 29, 289-299 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881114565144

29 Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology 235, 399-408 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x

30 Ross, S. et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol 30, 1165-1180 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116675512

31 Studerus, E., Kometer, M., Hasler, F. & Vollenweider, F. X. Acute, subacute and long-term subjective effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a pooled analysis of experimental studies. J Psychopharmacol 25, 1434-1452 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881110382466

32 Schmid, Y. & Liechti, M. E. Long-lasting subjective effects of LSD in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology 235, 535-545 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4733-3

33 Uthaug, M. V. et al. Sub-acute and long-term effects of ayahuasca on affect and cognitive thinking style and their association with ego dissolution. Psychopharmacology 235, 2979-2989 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-4988-3